"Frozen shoulder" - myths, truths and treatments. Part 1

A true frozen shoulder leaves women with pain and frustration. Google searches are unlikely to provide much comfort, with most well known sites stating that medical options, beyond pain relief and steroid injections, are limited, only the passage of time will resolve the problem and it can last for years! There’s light on the horizon.

With the right management pain can be less, the recovery time can be shorter.

What is a true ‘frozen shoulder’?

True frozen shoulder is hallmarked by initial pain, which may become protracted, then extreme stiffness and limited movement. Ultimately, there is a gradual ‘thawing’ phase, during which the movement becomes easier, which lasts from months to years. There's a big variation in time scales. To get resolution quicker, early diagnosis is key.

If you think you have frozen shoulder, the most important thing is to find out for sure. The right diagnosis means you can get the right management.

Changes in frozen shoulder over time. This pattern of progression comes from old studies.and doesn't reflect what happens to everyone.

The best way to get a formal diagnosis is an in person consultation with a GP, shoulder consultant or Physio. The gold standard management is to have an Xray to ensure there's no bony, joint or other issue responsible for the pain. Physios can also undertake tests to see exactly the direction of movement limitation. Limited side rotation, trouble lifting the arm out to the side or above your head and put your hand behind your back are hallmark signs.

What you will feel? Trouble lifting your arm, washing your hair, doing up your bra or putting on your coat.

This can happen alongside other shoulder problems, such as rotator cuff muscle tears or joint problems.

What is actually happening?

There's a change in the connective tissue in the shoulder, resulting in a thickening and contraction of joint structures, inflammation and scaring. It particularly affects the collagen (thick, strong connective tissue) in the coracohumeral ligament, making it thicker and tighter. Structures within the joint, such as rotator cuff tendons, can become compressed when you move your shoulder, making pain and restriction even worse.

A thickened, shortened coracohumeral ligament is a distinctive feature of frozen shoulder

What causes it?

We don't know for sure, but there are alot of factors which make it more likely. Women who are peri or early post menopausal are prime candidates for reasons we don’t fully understand. Over-reaching, lifting something that's just too heavy for you or recent upper body trauma, including breast cancer surgery or removal of lymph nodes under the arm, can increase your risk too.

There's an interaction between our metabolic systems and immune systems, the health of our heart and blood vessels, and joint and muscle health play a role. Diabetes and some cancer drugs can affect proteins and collagen in the shoulder joint and coracoacromial ligament too.

What is your wider health like? Sometimes women who are diagnosed with frozen shoulder will find that other markers of metabolic health, like blood pressure, blood sugar levels or cholesterol, have increased. Recent research links thyroid issues and Parkinson's disease with Frozen Shoulder too. It's worth finding out if you have any of these these often silent risk factors - see your GP if you have concerns about your wider health. Managing your wider health will help you manage your shoulder pain and stiffness too.

Being female, peri or post menopausal, shoulder injuries or having other medical conditions can affect your risk.

So why don't monkeys and apes get frozen shoulders?

Monkeys move their arms to survive and it seems they don’t stiffen up!

Like our tree dwelling ancestors, humans are made to move. Monkeys and apes move their arms to gather food and survive. It seems shoulder inactivity, through lifestyle or other causes, increases our risk of developing frozen shoulder. While I'm not suggesting we start swinging from tree to tree or reaching for bananas, exercising the arms and regular breaks from sitting will help prevent shoulder and other health problems.

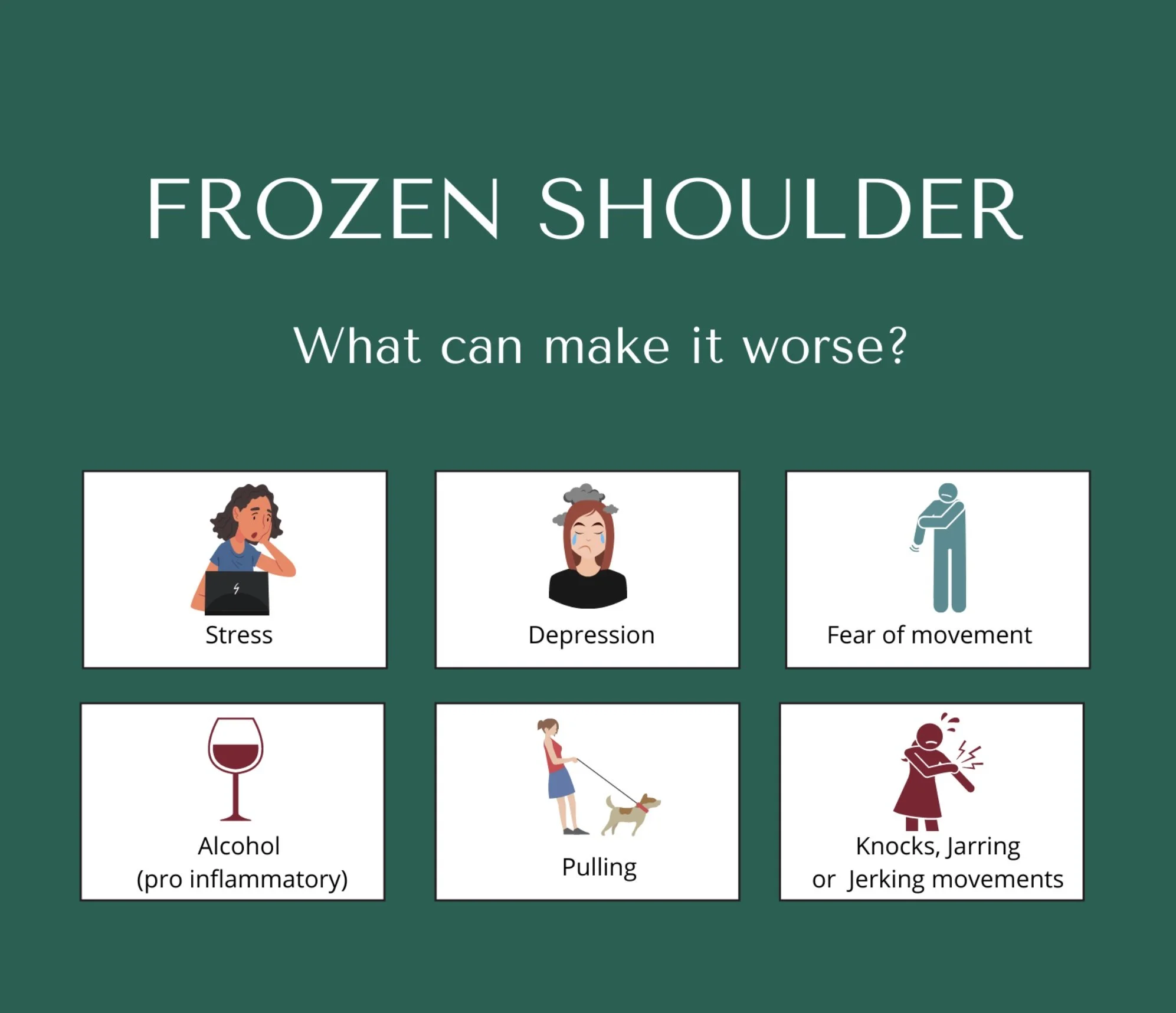

What makes it worse?

Stress, anxiety, feeling overwhelmed and depression can make this condition worse.

Being scared to move the arm is only natural, but not using it at all actually makes the joint even more stiff and sore. Move the arm gently and do daily tasks as pain allows. Gentle pendular movement is a good place to start.

Tempted to have a medicinal nightcap? It's also logical to think that a glass of wine or a nightcap will help if you're not sleeping . Sadly, the opposite is true, it can make inflammation and sleep quality worse. Quick movements also don't help either.

What to avoid or minimise if you have a frozen shoulder.

See Part 2 of this blog for my favoured exercises and top tips.

References

1. Hanchard, N et al. Physiotherapy for primary frozen shoulder in secondary care: developing and implementing stand-alone and post operative protocols for UK FROST and inferences for wider practice. Physiotherapy 2020; 107: 150–60. DOI: 10.1016/j.physio.2019.07.004

2. Hand GC, Athanasou NA, Matthews T, Carr AJ. The pathology of frozen shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2007; 89: 928–32. DOI: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B7.19097

3. Pietrzak, M. Adhesive capsulitis: An age related symptom of metabolic syndrome and chronic low-grade inflammation? Medical Hypotheses. Vol 88 2016: 12-17.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0306987716000141?via%3Dihub

4. Rangan, A et al. BESS/BOA Patient Care Pathways Frozen Shoulder. Shoulder & Elbow 2015: Vol. 7(4) 299–307. https://www.boa.ac.uk/uploads/assets/221d74d9-2db0-40c6-ae113e5b1bef68e5/frozen%20shoulder.pdf

5. Rangan, A et al. Management of adults with primary frozen shoulder in secondary care (UK FROST): a multicentre, pragmatic, three-arm, superiority randomised clinical trial. The Lancet, Oct 2020: Vol. 396, Issue 10256, 977 - 989. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31965-6

6. Zuckerman, J, Rokito, A. Frozen shoulder: a consensus definition. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2010; 20: 322–5.DOI: 10.1016/j.jse.2010.07.008