Musculoskeletal Syndrome of the Menopause

At a recent review, an active female patient shared her experience of sudden generalised joint aches and worsening knee pain, which had come on for no apparent reason. She asked, like many before her, “could it be menopause?”

The cluster of problems women commonly experience in midlife - generalised joint pain, frozen shoulder, greater trochanteric pain syndrome (previously considered as hip bursitis), tennis or golfer’s elbow, carpal tunnel and plantar fasciopathy (previously labelled plantar fasciitis), changes in muscle mass, strength and bone density, worsening osteoarthritis - have been given a name in a recent paper by Dr Vonda Wright and her co authors. The label: “Musculoskeletal Syndrome of the Menopause.” So what does that really mean and what can we do?

According to this paper, over 70% of all perimenopausal and menopausal women will experience pain, stiffness or problems related to bones, muscle and joints and 25% will experience severe symptoms.

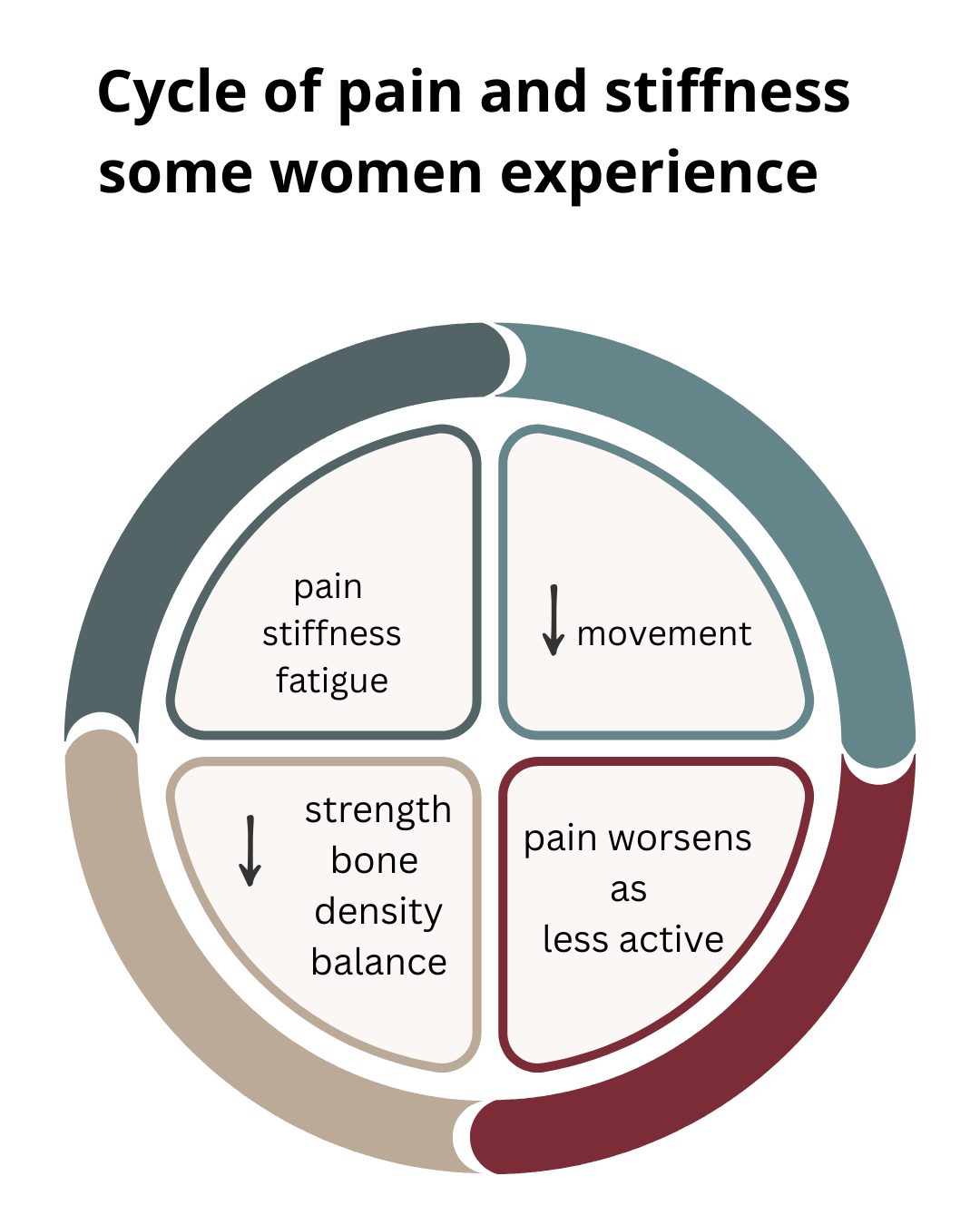

Women can get stuck in a cycle of pain, stiffness and sometimes, exhaustion. This in turn can impact work, family, self esteem and relationships, accompanied by personal and financial costs.

A constellation of processes

Wright’s research group refer to a constellation of processes that occur during perimenopause (when women start experiencing changes in their cycle). The acute drop in oestrodiol, the most biologically active form of oestrogen, impact bones, joints, muscles, tendons, ligamens, nerves, collagen and adipose (body fat). For most, these changes happen between the ages of 45 and 55, and the drop in hormones continues to impact women after this transitional period finishes.

Musculo-skeletal syndrome of the menopause: the effects in real terms.

Women still have to champion their own cause when speaking health care professionals and others about these problems, as they’re often overlooked, dismissed as a normal part of ageing. So much can be done to overcome these issues and support women in leading more fulfilled, active lives.

5 processes, 5 quick wins

An outline of the key processes and what you can do

Inflammation

More than half of perimenopausal and menopausal women have generalised joint pain, and this doesn’t necessarily correlate with joint issues on scans. Something else is going on.

Oestrogen helps regulate inflammation and has a role in preventing generalised joint pain. 17β-estradiol, the most potent biologically active form of oestrogen, inhibits release of inflammatory cytokines. Inflammatory cytokines can trigger or heighten inflammation, and diminish the muscles’ ability to respond to damage and function well, as well as promote accumulation of fat mass. Dropping oestrogen and increasing can leave women more exposed to generalised inflammation.

The result - women struggling to elevate their shoulders without pain, trouble sleeping on their side due to hip tendon changes, struggling with typing due to elbow, forearm and wrist inflammation and limping with heel pain.

5 quick wins

Understand what’s aggravating your joint or muscle problem

Maintain gentle movement, stopping short of severe pain

Support the affected area. Physios can help you understand what is best (and what not to waste money on!) e.g. a support for the wrist for carpal tunnel pain, a pillow between the legs when sleeping for outer hip tendon problems

Nourish yourself to support healing. See Laura Clark @menopause.dietitian’s guidance on menopause and gut health here

Practice self care. Stress and anxiety worsens inflammation, so support yourself with coping strategies.

2. Muscle pain, reduced muscle mass

Women lose 3 to 8% of their muscle mass every decade after age 30, with this loss accelerating to 5 to 10% after age 50. In late perimenopause and post menopause, women are much more likely to have sarcopenia (involuntary muscle loss). Finding it harder to grip the kettle or a weight? A bit tougher running up the stairs or hills? Menopause is a potential contributor.

This matters because loss of muscle mass and strength impact not just how we move and feel, but our ability to burn energy and risk of conditions such as diabetes or heart disease.

Have good quality sleep over 7-8 hours and for the most active women, schedule rest and recovery.

5 quick wins

Add inclines to regular walks/runs

Focussed resistance training, emphasising heavier resistance rather than lots of repetitions

Maintain flexibility

Ensure appropriate protein intake

Have 7-8 hours of good quality sleep, schedule rest and recovery

3. Loss of bone mineral density and resilience

Women have an average reduction of 10% in bone mineral density during perimenopause and menopause. The fastest bone loss starts about a year before your final period, stays accelerated ~3 years, then slows but continues post menopause. Being more active, be it through housework, gardening or regular exercise, is associated with greater bone strength and density, both before and during menopause. This directly affects risk of osteopenia and osteoporosis.

5 quick wins

Do weight bearing exercises, taking weight through arms and legs.

Lift heavier weights

Add impact. High impact exercise os better for bones, e.g. light jogging, adding vigour to a press up

Move in multiple directions, not just a straight line e.g. ball sports, tennis

Take Vitamin D in autumn and winter months. IT helps regulate calcium and phosphate uptake, and is recommended by the NHS.

4. Collagen, cartilage and connections

Oestrogen stimulates collagen production and turnover, helping to cartilage strong, and our ligaments (which support our joints) and tendons (which attach muscles to bone) resilient. As we get older and there’s less circulating oestrogen, the body is less efficient at repairing cartilage and tendon issues, which in turn can not only make women more prone to injury, but slower to recover. These changes also affect the pelvic floor, and can leave women more prone to leakage and other intimate issues.

5 quick wins

Treat injuries quickly. Delays can weaken joints and muscles further

Strengthen stability muscles around joints. Each joint has muscles crossing it which give control and stability. e.g. rotator cuff muscles around the shoulder.

Move a little, often, to stop joints getting stiff. Getting up from the desk regularly helps!

Cycling keeps the legs moving and lubricates joints

Do pelvic floor exercises, see a Specialist Women’s Health Physio if you have leakage, pain or problems

5. Reduced balance

5 quick wins

Practice standing balance in bare feet - eyes open or shut. Being bare foot allows us to use our feet in the way we were designed to

Yoga - I’m just about holding this pose for the picture but it can be hard!

Jump or hop. Remember skipping and hopscotch? They train us to be dynamic and respond to stumbles

Walk or jog on uneven paths

Try something outside your balance comfort zone. From dance to paddleboarding, there’s something for everyone. For more on this, see my blog on visiting a blue zone.

So is it just the hormones? What else is going on?

When it comes to our bodies, it’s never that simple. We’re products of our history - injuries, surgery and our experiences of pregnancy and childbirth (including caesareans, which cut through our abdominal muscles) shape us. Genetics, general health and lifestyle and the pressure on our joints directly affect us too. While generalised joint pain can be an independent menopausal symptom, research suggests that hormonal changes often compound pre-existing issues and vulnerabilities rather than cause the problem.

For example, if you have a grumbling knee problem, reduced ankle weakness from an old sprain, a stiff lower back and/or hypermobile hips or, like me, overuse your wrist and hands in your job or when gardening, the hormones can have an amplifying effect.

With oestrogen playing a huge role in keeping joints and tendons healthy, it makes sense that a drop in levels may play a part in tipping an old problem into an acute one.

Hormonal changes during menopause are not necessarily causing pain, but can compound the effects of other influences affecting joint and muscle health.

How hormone changes impact specific conditions like gluteal tendinopathy (outer hip pain), plantar fasciopathy, osteoarthritis and frozen shoulder is being explored, with mixed findings in recent studies, and there are many unknowns. What is certain is that moving well and consistent strength, fitness and balance work will help.

A unique opportunity to influence our future

Physios appreciate the interaction between your general health, changing hormone levels and age and how they affect your body. They can anticipate the onset of related symptoms and give you the tools to ward off future detrimental processes. They help work out what’s associated with perimenopause and what may be caused by other processes or wider health issues.

If necessary, we advise women to follow through with medical support wider menopausal symptoms, health conditions and diagnostic scans.

Was this content helpful? I love helping women understand their bodies and how to help themselves. You can engage me as a speaker, either in person, or online, for your workplace, women’s group or sporting body? Find out more here

References

Dufour, S. et al. Association between lumbopelvic pain and pelvic floor dysfunction in women: A cross sectional study. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice; Volume 34, April 2018: 47-53 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msksp.2017.12.001

Blumer et al. 2023. Arthralgia of the menopause - a retrospective review. Post Reprod Health. 2023 Jun;29(2):95-97. doi: 10.1177/20533691231172565. Epub 2023 May 1

Bondarev et al. Physical Performance during the menopause transition and the role of physical activity. 2021. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci Aug 13;76(9):1587-1590. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glaa292

Douglas-Harris, M and Ramaskandhan, J. Menopause and plantar heel pain: a ppi and co production journey. 2024. Newcastle Biomedical Research Centre. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/393281614_Menopause_and_Plantar_Heel_Pain_A_PPI_and_co_production_journey

El Khoudary, S, et al. The menopause transition and women's health at midlife: a progress report from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Menopause 2019: 26(10)

Gulati et al. The influence of sex hormones on musculoskeletal pain and osteoarthritis. The Lancet. April 2023. Vol 5 Issue 4.

Isenmann et al. Resistance training alters body composition in middle-aged women depending on menopause - A 20-week control trial BMC Women's Health volume 23, Article number: 526 (2023)

Kang et al. Effect of Sedentary Time on the risk of orthopaedic problems in people aged 50 years and older. The Journal of nutrition, health and aging. 2020. Vol 24 (8) pp 839-845. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1391-7

Karlamangla et al. Bone health during the menopause transition and beyond. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2018 Oct 25;45(4):695–708. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2018.07.012

Lu CB, Liu PF, Zhou YS, et al. Musculoskeletal pain during the menopausal transition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neural Plast. 2020;2020:8842110–8842110. doi: 10.1155/2020/8842110

Chan S, Gomes A, Singh RS. Is menopause still evolving? Evidence from a longitudinal study of multiethnic populations and its relevance to women’s health. BMC Womens Health. 2020;20(1):74. doi: 10.1186/s12905-020-00932-8.

Rothschild C and Collingwood T. Maximising Running Participation through menopause. Journal of Women's & Pelvic Health Physical Therapy 47(2):p 133-143, April/June 2023. | DOI: 10.1097/JWH.0000000000000276

Saltzman et al. Poster 188: Is Hormone Replacing Therapy Associated with Reduced Risk of Adhesive Capsulitis in Menopausal Women? A Single Center Analysis. Orthop J Sports Med. 2023 Jul 31;11(7 suppl3):2325967123S00174. doi: 10.1177/2325967123S00174

Volpi et al. Muscle tissue changes with aging. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2004 Jul;7(4):405–410. 10.1097/01.mco.0000134362.76653.b2

Wang et al. Mechanistic insights into the anti-fibrotic effects of Estrogen via the PI3K-Akt Pathway in Frozen Shoulder. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 2025 p.106701. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2025.106701.

Wright et al. Musculo-skeletal Syndrome of the Menopause. Climacteric Oct 2024.27(5):466-472. doi: 10.1080/13697137.2024.2380363.

Williams et al. Hormone replacement therapy (conjugated oestrogens plus bazedoxifene) for post-menopausal women with symptomatic hand osteoarthritis: primary report from the HOPE-e randomised, placebo-controlled, feasibility study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2022 Sep 21;4(10):e725-e737. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(22)00218-1